“Probably one of the most private things in the world is an egg until it is broken.” — M.F.K. Fisher

My mother came into my bedroom when I was eleven years old to show me how much blood I was going to lose each month; she carried the little glass measuring cup by its handle, the one I used to measure buttermilk before I cracked in and whisked an egg for biscuits on Sunday mornings. She had filled it with water to the red quarter-cup line; it sloshed. I burst into tears; everything was heading in the wrong direction; I wanted to go back to bleeding single drops. †

“It’s only four tablespoons,” she said in exasperation, like a slap; get over it.

My period started during school, on a Tuesday; I was thirteen. I bled through my underwear and jeans. The lunch bell buzzed over the loudspeakers; and then came the gun-shot sound of metal locker doors banging open and closed. Standing in a narrow stall in the girls’ bathroom, I packed layer upon layer of folded one-ply toilet paper between my skin and the fabric; it soaked through immediately; lamely I bunched in another handful of tissue and tugged up my pants.

Tuesdays we went to Ristorante Italiano for dinner: faded murals of Italian streets on every wall, red tablecloths, straw-basket chianti, early-bird special linguine and clams; we drove straight from school. My proud mother proclaimed to the favorite server, Anne, that my period had started; and then led me to the bathroom and bought me a pad from the quarter dispenser on the wall and showed me how to attach it to my underwear; bulky, crude: a relief. At the table, I pried open the steamers: mussels and clams; I pressed a chunk of my garlic bread into the liquid at the bottom of the dish and watched it swell and absorb. Anne brought me a piece of cake with a candle in it.

Twenty years later, after I birthed my daughter in my husband’s bed in the middle of the night, I birthed the placenta; it looked like a porterhouse steak. I could not really stand in the shower and so the nurse held me up. Blood swirled the drain. I slept the three hours until dawn. The next day, terrified, I begged my husband to stay with me and he said No and left for work. The baby napped on the bed; after a long time I steeled myself to walk to the kitchen. Outside, it snowed.

The previous week, round-bellied, still under the dream-spell of pregnancy; I had baked and frozen individual chicken pot pies in preparation for this part. I had made an all-butter crust, and rolled it out and draped it over ramekins of diced carrots, pearl onions, and the chopped meat. Breast meat, picked from the previous night’s bird after we had eaten the legs. My knife fell against the parsley, and I smelled the clean pepperiness of it, faintly like wet lawn. I simmered the carcass all day to make stock and then reduced it to gravy. I had brushed beaten egg over the tops of the little pies before I baked them. How I had loved to cook. Now I looked at them, carefully stacked in the freezer. I was not the least bit hungry. I had eaten diligently for nine months to grow the baby inside of me and now I would eat in order to make milk to keep the baby alive.

Weeks later, my husband cooed to our daughter, who eyed him from where she nursed. When I spoke; he spoke to her, never looking at me. He said, “Why is your cow talking?”

She hardly slept; mostly she cried. My husband did not want strangers raising his child: no daycare; no babysitters. I stayed home. I applied for food stamps; I applied for government health care for the baby. The crisis line had a busy signal. The baby only slept when she was latched on to my breast. If I moved, she screamed. One week, I slept thirteen hours: a new low.

The summer before my daughter turned two, my husband took over putting her to bed; I was inept. In a huff, he emerged from her room at half-past seven— the baby laid awake and bawling— and announced he really wished we had a much bigger house with a separate wing for the bedrooms, away from the noise of the kitchen.

I thought to myself: I am going to stop cooking dinner for you.

I had learned, even before then, to grind my coffee before I went to bed at night; and not to wake him for anything, ever.

One evening, we went to dinner with some of my old friends, and when they asked me about parenting I said matter-of-factly that the year after my daughter was born had been the worst year of my life. My husband glared; I shrugged.

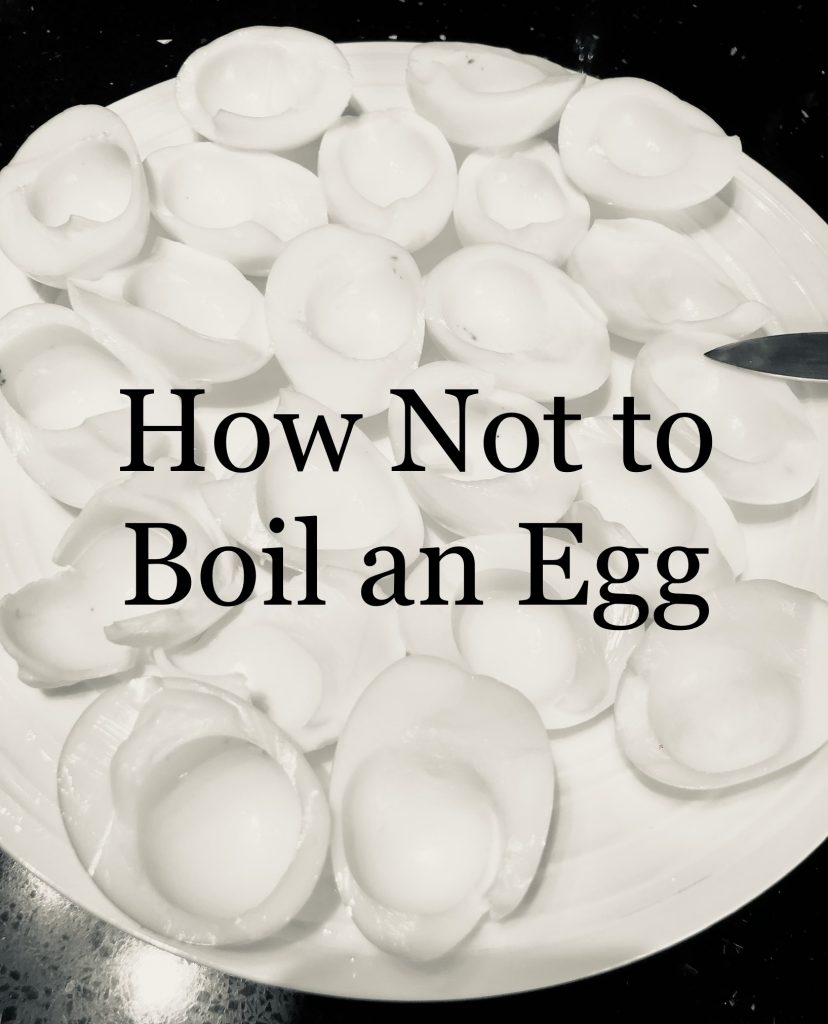

A few years later, for my mother’s seventieth birthday party, she asked me to make deviled eggs. The day before my daughter and I arrived, my mother boiled three dozen eggs; she took them out of the refrigerator so my sister and I could peel them. There are mainly wrong ways to boil an egg: too vigorous a boil, too fresh an egg, too long in the pot; and they must be shocked in ice-water immediately. My mother, wary always of salmonella, cooked them to death; they were gray-green around the yolk. My sister and I cracked egg after egg, and the shells refused to peel away from the dull rubbery white inside; big chunks sheared off or chipped away. Our three daughters played underfoot: I had, by then, divorced my husband; and hers was off who-knew-where. My sister and I laughed and talked as each egg turned out somehow worse than the last. You get used to doing the things that have to be done; you get used to the violence of womanhood. The egg, unbroken, eventually is no more than a shell around something dead.

The following year, when I woke from anesthesia after tubal-ligation surgery, the nurse sitting beside me in the recovery room fed me chips of ice. She was telling me about her backyard chickens, she had twenty; I came to mid-story, as she was listing them: Buff Orpingtons, Rhode Island Reds. Araucanas.

“Araucanas,” I said dreamily; I barely knew where I was, “My mother used to raise Araucanas.”

I lifted the edge of my gown; there were three small squares of gauze taped to my abdomen. One covering my navel, where the scope had been, and one roughly over each ovary.

I smiled up at the nurse. I said, “Their eggs were the prettiest blue-green.”

† (Around this age (11) I began to suffer hour after hour-long nosebleeds; regularly choking and nearly drowning or suffocating under the unstoppable fast horrible hot salty rich meaty metallic thickness of my own liquid body pouring out imperfectly as I tried to hold my breath or tilt my head or pinch my nose or lean forward or lean backwards or lie down or do whatever the current adult advised; and while they were gone frantically trying to find a roll of paper towels or toilet paper or a bag of cotton balls or an old towel, I would just sit there and swallow and swallow my own blood; stoic, barely breathing, feeling my self liquefying and refilling, dizzy and blunt and blood-spattered and going dark at the edges as my stomach churned wet and everything else shadowed.)

Author: `aqaq`

Tasia Bernie is an essayist, and editor of FeederPDX.com. She enjoys used bookstores, offal, and hard laughter. She is a very good eater. She lives with her daughter and two orange cats in Portland, Oregon.