After college, I packed my car and moved across the country to go be in love in Ohio. Six weeks later, I called my mom and asked her to come get me. She flew out and we drove home. On the road, I ate almost nothing. For the first time in memory, I had no appetite. Like a little kid, I ate raisins from tiny red boxes. We stopped at diners. I ordered banana pudding; even that I barely touched. By the time we reached California, I fainted from stomach pain if I tried to eat anything at all.

I sat alone on the examination table in a thin gown. The doctor knocked gently and entered the room. He helped me lie down. He touched my stomach. He asked what I’d been doing since college; I told him about the move. He listened to my heart. How much weight I had lost? I remember the word peristalsis. The possibility of stomach problems impacting the heart. Irregular heartbeat, atrial fibrillation. He was talking while moving the stethoscope over my chest and abdomen; pausing, listening. He helped me sit up. The paper crinkled under my legs.

“Your heart is broken,” he said.

I was caught so off-guard I burst into tears.

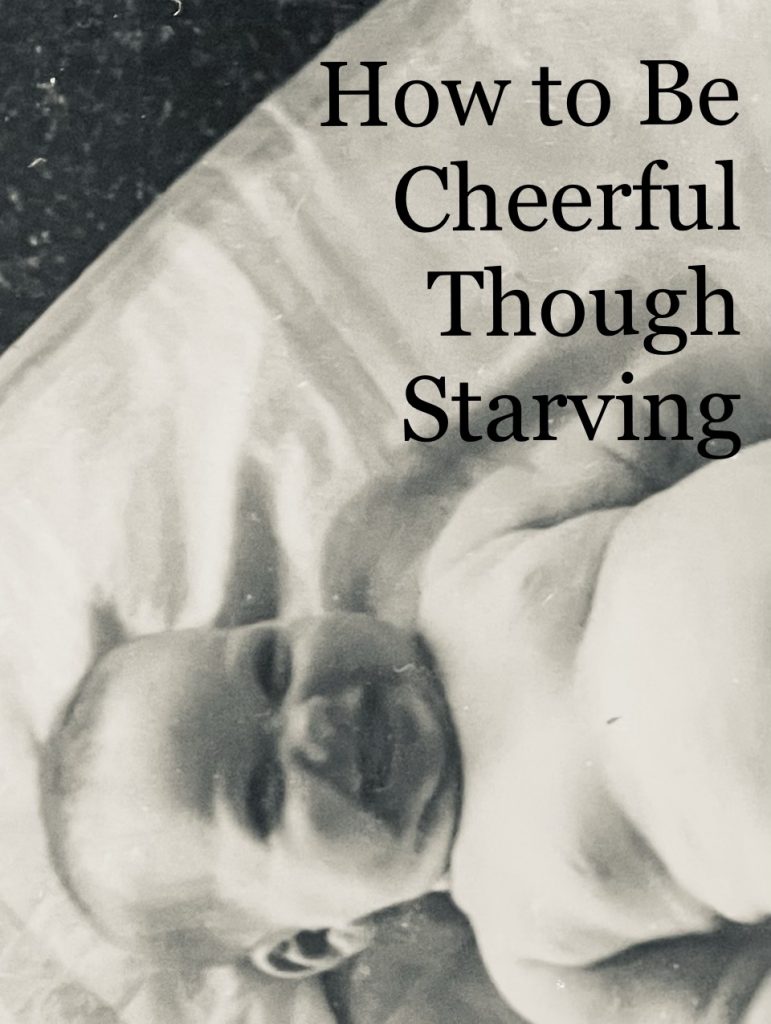

In my baby album, there is a full page of photos: a half-dozen snapshots of me at six months old; I am lying on a blue blanket on our Spanish-rice- colored shag carpet. I was an exceedingly fat infant; my parents called me the Michelin Tire Baby. My belly is a half-globe, a dome, a shield. Giant rolls of fat heavily ring my thighs. There are so many thick bands of fat on my arms that each arm could have been modeled from its own can of biscuit dough. In every photo, I am grinning, squirming. Also on this page is my first fortune-cookie fortune, which my parents saved, and slipped under the plastic. It reads: “You will never know hunger.”

I had met this man, who turned out to now be my doctor, when I was ten years old. I was surprised when he stepped into the examination room: he was out of context; I also had never known his name. In the years before I moved north for college, I had seen him regularly; he ordered an afternoon cappuccino from the café in the bookstore where I wrote after school. The first time he sat down across from me at my little table, I covered my notebook with my arm. He leaned in, holding his coffee, and shook his head slightly, to tell me he was not trying to read what I was writing. Instead he said, “What do you write about?”

I had his attention; I have no memory of my answer, only of the nervous pleasure of being listened to fully.

The café had cookies: giant buttery pecan sandies, each an inch thick and piped with a rosette of fudge in the center; my god. I ate them always in a careful circle of bites, saving the dark chocolate for last.

I dressed. The doctor met me in the hallway. He gave me antispasmodics; little mint-flavored melt-aways, to help with the cramping and pain.

“I wish there was more I could do for you,” he said. “If there’s anything you can think of that might give you some relief, I’ll prescribe it…” He thought for a moment, “It’s not uncommon to treat things like this with Xanax. If only to take the edge off stress around eating.”

“Okay,” I said. “I can try that.”

“Just don’t go selling it near Lincoln. My nephews are in school up there.”

I smiled at this; he knew my neighborhood.

“Drop by later this week. The bloodwork will be back in a day or so, any time after that is fine. Or if things get worse, or change significantly, come in.”

I nodded. I wouldn’t be staying with my mom much longer; I didn’t know when I’d return to Oregon.

He continued, “And I don’t want you to make an appointment. I don’t want you to make appointments at all, actually. Just bring me a cappuccino and walk on back. My office is over there,” he pointed down the hall. “I’ll let the front desk know.”

I still could not eat. In line at the post office the next morning, I fainted. I came to; at first I could not hear anything. The floor felt very cold. Without moving, I surveyed the room from where I had crumpled. People had stepped around me, and over me, to make their way to the counter.

The bookcafé had a familiar smell: new books, good stationary, printer’s ink, and cinnamon. When I was in middle school they had employed one particularly-overburdened barista. She invariably forgot she had started toasting the sourdough roll served alongside my salad until the roll burnt; there was no timer on the toaster. The silver-haired owner, smelling smoke, ran from the back of the store and swooped behind the counter to rescue the roll. She tugged it on to a plate and buttered it vigorously, always declaring, “I love burnt toast,” before disappearing, with plated roll, to her office. I loved her; she gave me a bookselling job when I came back from my first semester of college, and rehired me every year after.

The following afternoon, I brought the doctor his cappuccino, in a petite paper to-go cup. I sat in his office and waited. I read the ornately-framed diplomas on the wall. There were several.

“Are you still writing?” He asked when he came into the room.

A warm feeling; he remembered.

“Yes,” I said.

“Good.” He opened my chart. The bloodwork. My lab results.

“Is that a heating and air-conditioning certificate?” I asked.

It was displayed in the same kind of heavy, gold-painted, carved-leaf frame as his Columbia diploma.

“When I emigrated to the United States,” he said, “I came with nothing. I had taken classes at a trade school, but I wanted to be a doctor. I had no money… so I told the university I would do all of their maintenance in exchange for tuition. They agreed. Because I was a good student, after that I earned scholarships and went on to Columbia and Stanford. Without that,” he said, pointing behind him with his pen at the HVAC certificate, “I would not be here. I don’t know his name, but whoever that person was who let me pay by fixing the ductwork? He changed my life.”

“That’s wonderful,” I said.

He nodded. He studied the chart, and cleared his throat. “What’s wonderful, and also not, in a way, is that your tests all came back normal. I can’t tell you that there isn’t something wrong, but…we know less about the gut than about deep space.”

“That’s okay,” I said; I had not misunderstood the original diagnosis.

“Send me some coffee beans when you get back to Portland, okay?” he said.

“Sure,” I said.

“You know where to find me.”

I drove home to Portland the following week. I shopped only for the ingredients I needed to make a sandwich. The sandwich from being in love in Ohio. The bread was dense, whole wheat; better if homemade. He had spread one piece of bread with cream cheese, and the other with natural peanut butter ground by the machine at the co-op. The honey had crystalized in the jar; it was thick and crunchy and was applied in a solid layer over the peanut butter. He had scooped a handful of chopped dates on to the cream cheese, and then pressed the sides of the sandwich together. We had lived on his farm in the mountains of Appalachia; the most beautiful unspoiled wilderness I had ever seen.

I ate small bites of the sandwich. I cried. Both things took a long time to finish.

Author: `aqaq`

Tasia Bernie is an essayist, and editor of FeederPDX.com. She enjoys used bookstores, offal, and hard laughter. She is a very good eater. She lives with her daughter and two orange cats in Portland, Oregon.